By Drazen Jorgic

MEXICO CITY, Feb 22 (Reuters) - Mexican drug lord Nemesio Oseguera, commonly known as 'El Mencho,' infamous for the bloody trail of bodies he left behind in battles with government forces and rival gangs, died in a military raid on Sunday.

An ex-police officer, Oseguera, 60, was the shadowy leader of the powerful Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), an international criminal enterprise widely viewed as one of Mexico's most powerful.

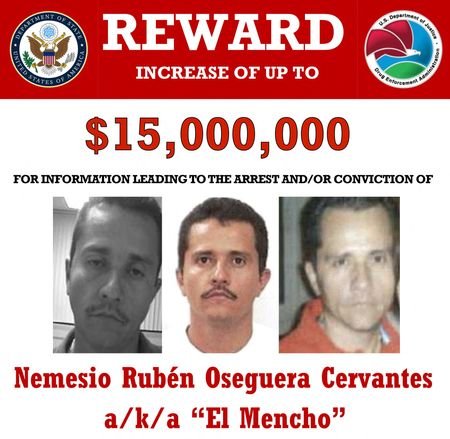

Over a relatively short period of time, Oseguera masterminded the CJNG's emergence as a criminal empire rivaling his former allies in the Sinaloa Cartel. He managed to evade arrest for years despite a $15 million bounty from the U.S. for information leading to his arrest or capture.

CJNG has been blamed for smuggling vast quantities of drugs into the U.S., including the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which has been linked to hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths in recent years.

"Apart from the heads of the Sinaloa cartel, 'El Mencho' has been the biggest prize for many, many years," said Vanda Felbab-Brown, a security expert and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

"And it’s really stunning, just like the heads of the Sinaloa cartel, how long he managed to evade U.S. and Mexican law enforcement gunning for him.”

BEHEADINGS

Arguably Mexico's most influential crime boss after captured kingpin Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman, now in a U.S. prison, Oseguera diversified into rackets such as stolen fuel, forced labor and human trafficking.

But unlike Guzman, who became a media celebrity, El Mencho preferred to remain in relative obscurity. He achieved notoriety for expletive-laden recordings leaked on social media in which he threatened enemies and officials.

Oseguera was also known for evading capture in spectacular fashion. In May 2015, as Mexican forces closed in on him, his tipped-off henchmen shot down a military helicopter with a rocket-propelled grenade to give their boss time to escape.

Targets of his hit men were rarely so lucky. His gang routinely employed beheadings and other gory means of intimidation.

In one six-week period in 2015, the gang killed two dozen police in western Mexico as a warning to authorities.

In 2020, Mexico City's then chief of police Omar Garcia Harfuch survived an assassination attempt that killed two of his bodyguards in an attack authorities blamed on the Jalisco New Generation Cartel. Harfuch is now the country's security chief and helped oversee the operation against Oseguera.

Oseguera was born in 1966 in a poor village in the mountains of the rugged and notoriously lawless western state of Michoacan. There, cultivation of opium poppies and marijuana have competed with avocado production for decades.

As a boy, he worked the fields, and later went to seek his fortune in the U.S., where prosecutors said he got into the heroin trade. After a few years, he was arrested and served time in a U.S. prison.

He was deported back to Mexico, where he joined the police before entering the Milenio Cartel, a satellite of the Sinaloa Cartel. Eventually, he became a top enforcer after stints as a sicario, or cartel assassin.

After a failed attempt at taking over the Milenio Cartel, he struck out alone, declared war on Sinaloa, and founded the CJNG in alliance with a local gang of money launderers.

The cartel is named for the western state of Jalisco, home to one of Mexico's largest cities, Guadalajara.

The CJNG mixed Sinaloa-style drug trafficking and community outreach with the ultra-violent methods of the Zetas Cartel, a gang that used paramilitary tactics to diversify into criminal enterprises such as extortion and kidnapping.

For years, Oseguera paid off police to cover his back as he operated with near-total impunity inside Jalisco. He also sought political protection.

"El Mencho's Jalisco New Generation Cartel was one of the biggest buyers of politicians and political campaigns, which has given it an enormous social base," said Edgardo Buscaglia, an organized crime expert at Columbia University.

Noting El Mencho's ability to win public support, Buscaglia pointed to footage broadcast during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic of people lining up for CJNG-stamped food packages handed out by cartel gunmen, not government workers, to help cushion the economic blow of lockdowns.

"Compared to the Mexican government," said Buscaglia, "he was the least bad option."

(Reporting by Drazen Jorgic, Laura Gottesdiener and Emily Green; Additional reporting by Stephen Eisenhammer; Editing by Christian Plumb and David Gregorio)